An Arthurian Slow Way down the Usk, from Caerleon to Newport, with tree-loving author Matthew Yeomans

An extract from Matthew Yeomans’ book, Return to my Trees.

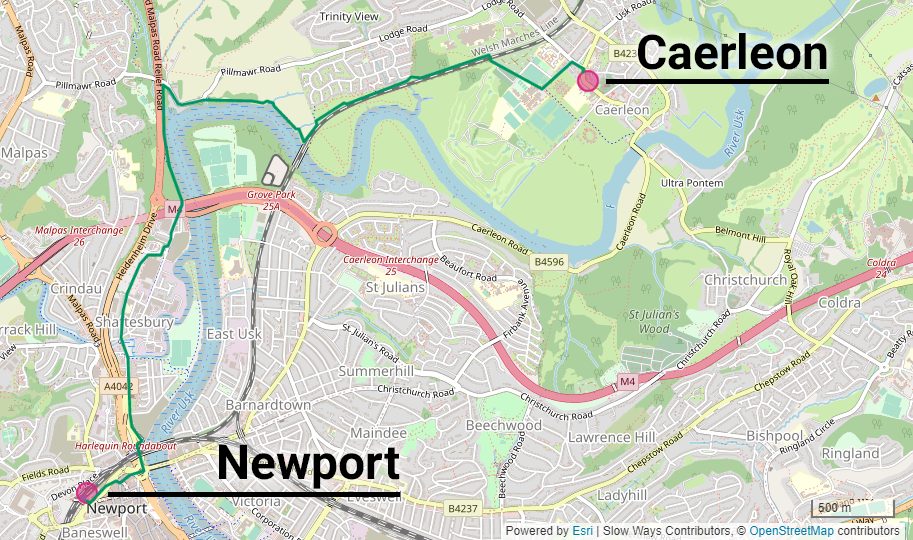

“This morning’s walk was to be a leisurely stroll from Caerleon, following the path of the River Usk to Newport. Heading into Wales’ third largest city might sound like a counterintuitive route for a National Forest trail, but part of my challenge was to imagine a walking route that might inspire people to reconnect with nature, and to understand that we can make that connection even when walking in urban environments.

I’d been inspired by the new grassroots walking initiative Slow Ways. It hopes to create a network of accessible walking routes that connect all of Great Britain’s towns and cities through crowdsourced mapping. Already, during the lockdown some 700 volunteers from

across the UK had collaborated to map out Slow Ways’ 7,500 public footpaths and rights of way that collectively stretched for over 110,000 km. I thought some of my routes might help add to that map.

For all these reasons I was keen to explore the relatively new cycle and walking trail linking Caerleon to Newport and to see how easy it would be to connect with the well-established network of canal walking paths that link up through east Wales.

Today I was joined by an old school friend called Andy. He lived nearby in Chepstow and his family hailed from Newport, so he was keen to explore his roots. We started by the Hanbury Arms pub in Caerleon and walked past the impressive stone remains of the old Roman amphitheatre. A group of young kids played hide and seek amid the grassy ruins while their parents chatted and drank coffee.

The Romans were a dominant presence in south Wales for nearly 400 years, and Caerleon played a major role in their control of western Britain. Even after the Romans left, Caerleon’s reputation was further enhanced by tales that it was King Arthur’s seat of power, where he gathered his knights at the fabled round table. The Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson travelled to Caerleon when he was writing his Arthurian poem Idylls of the King. He stayed at the Hanbury Arms pub and took long walks for inspiration along the river Usk.

The river path led us past Caerleon scout hut, the local football club and the high school, before crossing a railway line and turning toward the Usk by the grand red-brick Victorian façade of St. Cadoc’s Hospital. Local people were out walking their dogs and a small cohort of cyclists rode by on their way to Newport. One was particularly keen to announce his presence: an elderly man dressed in a bright yellow top who rang his bell with great urgency as he sped by us.

Our conversation turned to the houses we had walked past. They were built on the floodplain no more than 100 meters from the banks of the Usk. Earlier in the year, the river had burst its banks during winter storms, flooding low-lying fields and prompting local authorities to lay down emergency flood barriers to protect residents. I wondered how these houses had fared during that storm surge, and how desirable this location would be in future as climate change further increases flooding. In spite of humanity’s best and worst attempts, nature always restores its own balance.

We were at the river now. It was high tide and the Usk looked picture postcard pretty as the sun broke through the clouds in streaks and reflected off the surface. A black cormorant was doing aerial reconnaissance for its lunch above us. This was the river in its best light. This far downstream the Usk’s waters begin to merge with the greater Severn estuary and the river displays a split personality. At low tide, it is reduced to a thin channel fighting its way through clogging, dirty grey mud banks that trap the little boats moored by its banks until the Severn surge frees them again.

Caerleon was well behind us at this point. We’d entered a sliver of countryside separating the town from Newport’s industrial edges. Even so, it was a surprise to come across a sow and her litter of piglets sleeping on the dry mud at the side of the cycle path. Behind the pigs was a truly magnificent and very old tree growing precariously at an angle out of a steep hillside, its thick branches raised upwards as if to help it maintain balance.

“So, what type of tree is that?” asked Andy with a hint of mischief.

“I’ve not quite reached that level of expertise,” I replied a little defensively. “However, I did download this handy Woodland Trust app with its guide to British trees. It should give us the answer.”

Just then an elderly couple walked around the corner: locals out for their daily constitutional up and down the river path.

“We’re trying to work out what type of tree this is,” I said. “Can you help?”

The couple looked at me as if I was a complete idiot.

“It’s an oak tree. Obviously,” said the woman before quickly moving on.

“Probably best not to tell too many people you’re writing a book about trees just yet,” said Andy.

Sustrans: Route 88

- Walk Caerleon to Newport yourself on Slow Ways route Newcae one

- Explore more Slow Ways routes from Newport

- Discover more Slow Ways routes from Caerleon

- Follow Slow Ways on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram

Matthew Yeomans

Matthew Yeomans is the author of a new book, Return to My Trees, that recounts his 300-mile walk through the woodlands of Wales exploring how we reconnect and restore balance with nature. It is published by Calon Books.