Ben Porter’s step-by-step beginners’ guide to recording wildlife and contributing to citizen science projects, plus tips for the nervous

As a passionate nature enthusiast and ecologist, getting out for a walk is as much about engaging with the wildlife around us and exploring the natural world as it is for the adventure, the physical challenge or the social element. Whether on a short local walk, or a longer Slow Way between towns and villages, my antennae are tuned into the unending dramas and characters of nature. I always carry my notebook, always eager for outdoor discoveries.

For enjoyment of the natural world, and a barometer of the landscape’s health

Although this is largely for the enjoyment of the natural world, recorded sightings from nature enthusiasts wandering around the country can provide invaluable data for assessing our nation’s biodiversity, a barometer of the landscape’s health. Changes in birdlife, plants and insect populations across the country are increasingly possible to gauge through ‘citizen science’ projects, such as the RSPB’s Big Garden Birdwatch.

What if people walking Slow Ways routes used these pathways as wildlife transects across the country?

Step 1: choose a Slow Ways route or a section to cover

The first step is to decide on a walk for your nature-recording adventure. You could choose a route on your doorstep that you know well, or pick one when you’re visiting another area to add an extra layer of discovery to your trip. Take a look at the national Slow Ways route map and find one that works for you.

Recording wildlife as you walk can add a bit of time to your journey, so it’s worth starting with a walk or a Slow Ways route that you’ll be happy covering in the time you have available. You could just choose a section to focus on, for example, which provides a sample of the route that you can repeat next time you visit.

Step 2: choose a wildlife group or species you’d like to focus on

A lot of people might be daunted at the sheer diversity of species and taxonomic groups within the natural world, especially in the verdant explosion of life in spring and summer. For those just beginning to identify the wildlife around them, I’d encourage you to start small and focus on a particular group or species. There are a wealth of different citizen science projects you could contribute to, depending on what most interests you, or what habitats your journey takes you through. Here are some suggestions to get going with:

• Birds: an accessible and relatively easy group to start with for your journey into recording biodiversity. You could record the number of species you see along a Slow Ways route, or make finer scale observations of nesting behaviours or abundance of species across the seasons, and submit these records to the Birdtrack app, run by the British Trust for Ornithology.

• Bumblebees: the BeeWalk is a volunteer-based bumblebee monitoring project organised by the Bumblebee Conservation Trust. This survey sees BeeWalkers walking the same fixed route (transect) once a month between March and October, counting and identifying any bumblebees they see. You could integrate this into a section of your Slow Ways route if you’re particularly passionate about bumblebees!

• Nature’s calendar: climate change is wreaking havoc on the pattern of seasonal events which unfold in the natural world, from the appearance of the first patch of frogspawn in your garden to the ripening of the first blackberries in summer. The Nature’s Calendar initiative run by the Woodland Trust invites members of the public to submit sightings of key events in nature through the year, allowing scientists to understand how climate change is affecting the timing of such events in nature. When you’re out on a Slow Way and tuned into the natural world around you, making note of flowers coming into bloom, leaves bursting from their buds, or the first summer migrant Swallows swerving overhead; it’s all valuable data to contribute to this project.

• Ancient trees: the Ancient Tree Inventory is coordinated by the Woodland Trust, which collates records of any old or ancient trees in our landscape. By getting these gnarled beacons of biodiversity mapped, it can help protect them from destruction and development. By keeping an eye out for particularly old trees when you’re out on a Slow Ways route, you can help build up the national map of these veteran trees.

Besides these examples, you can also use more general recording platforms like iRecord and iNaturalist to log your sightings of insects, plants and animals you see whilst you’re out walking, and these will be sent to the appropriate records centres in your region to be integrated into the National Biodiversity Network. It’s great to record your wanderings for Local Environmental Record Centres.

Step 3: recording what you see

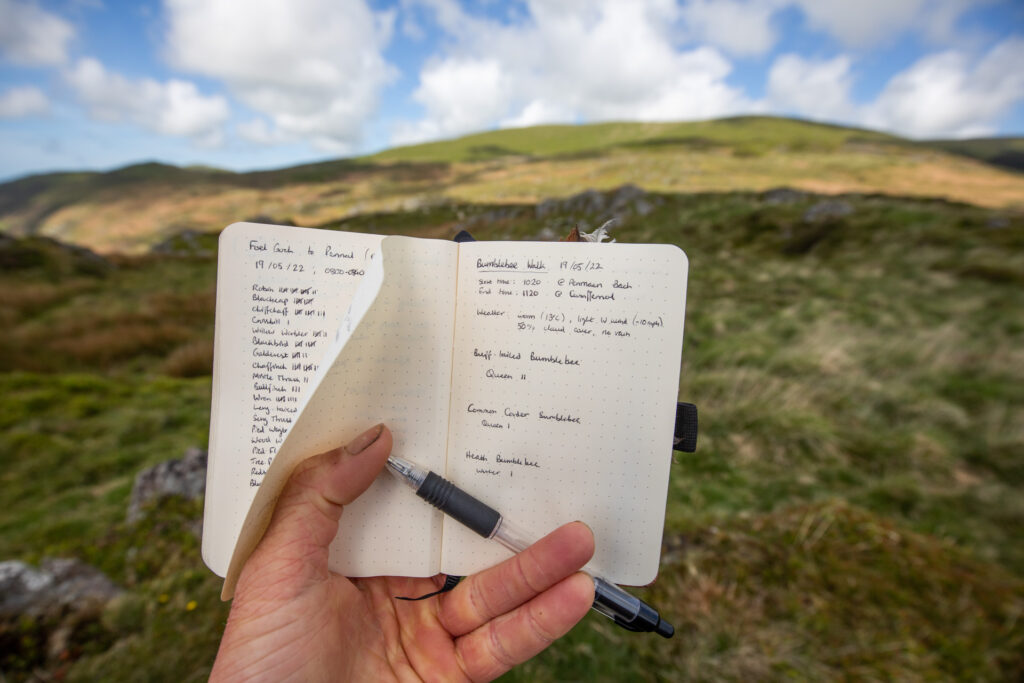

With your route decided and recording focus in mind, let’s head out for a walk and see how it can work in practice. There are two main options for how you go about recording the species and wildlife you see whilst you’re out and about. The first, perhaps old-fashioned way (but still my preferred!), is to use a notebook. A small notebook in your pocket is an invaluable accompaniment for any walk, jotting down the species you see, the numbers you’ve seen, and any notes on behaviours, locations, interesting sightings, and even a little sketch of something you’re not too sure of. You can then submit these records afterwards, once you’re back at home and able to confirm some of the identification difficulties you might have been unsure of. I’m a prolific notebook user, and have been keeping almost daily lists of the birds I’ve seen since I was about ten years old!

Smartphones – very useful, but sometimes getting away from a screen is the purpose of a walk!

The second method, which has advanced incredibly over the last few years, is the use of smartphones. You can now record your sightings out in the field and upload them directly to platforms like iRecord and iNaturalist, perhaps even with an accompanying image to back up the identification of species if needed. A wealth of other recording apps, sometimes specific to the project (such as those mentioned above) can also be downloaded onto your phone and used in the field.

You can also use your phone to assist with the identification of trickier taxonomic groups– apps like Seek provide an amazing tool for identifying plants, animals, insects and birds, simply by pointing your phone at a subject and seeing what species it identifies it as. This should be treated with some caution: not all species can be easily identified without closer scrutiny of specific features.

Similarly, apps like BirdNet allow you to record an unfamiliar birdsong and have its identification distinguished by the phone. This can be really helpful for learning and for recording, but relies on having a phone with you, and for many, getting out for a walk is somewhere we’d like to be off our screens and connecting with nature!

Step 4: submitting your records

Once you’ve been out on your meander and recorded the gnarled trees of ancient oaks, buff-tailed bumblebees and butterflies in an area of diverse and fragrant wildflower meadows, it’s time to get this data to the projects that need it. If you used a phone whilst you were out in the field, then the records can often be uploaded directly to the appropriate platform whilst out or shortly after returning; but for the notebook method, we’ll have to spend some time submitting records to the appropriate database.

I usually sit down with a cuppa in the evening after a day’s walk, go through my notes and get my laptop fired up to send in all these sightings. This can be a great way of reminding yourself of certain species you saw during your walk, looking up their identifications, reflecting on the wildlife you saw and sharing your sightings online, such as in Facebook identification groups if further help is needed. Platforms like Birdtrack and iRecord are my go-to record databases, and it takes just a few minutes to enter in the date, location, species and numbers from your outing. You can also use more localised recording groups that are part of the UK National Biodiversity Network, or by finding your Local Environmental Record Centre.

Step 5: repeating through seasons and across years

Whilst there’s a lot of value in having data submitted from a single walk or Slow Ways route, it’s even better to have data from repeated visits to these routes, across the seasons and over several years. This will weave together a much clearer picture of what species are where, when they emerge, how they’re faring and potential changes in their populations and distributions over time.

Projects like the BeeWalk ask you to walk your chosen transect route each month through the summertime: this helps to reveal how the assemblage of bee species changes over the season. By visiting a local Slow Ways route often, you’ll be in a better position to accurately record when you notice the first flowers flowering in spring, or the first Chiffchaffs singing in March; valuable information for a project like Nature’s Calendar. And besides the value for recording, visiting a walk or patch regularly helps you really get to know the area on a deeper level. You develop more awareness of the wildlife in these places when you visit regularly, noticing the subtle changes week-to-week.

But how do I know what it is? A few tips if you’re nervous to identify

For many people starting their journey in discovering the immense world of nature on your doorstep, it can be hard to know where to begin; there’s so much to see, so many different species, a boggling list of scientific names, and so many lookalike creatures to distinguish… it can be overwhelming. You may lack the confidence to identify a plant, animal, bug or beetle, and be hesitant to submit records. For those who feel this way, here are a few suggestions for starting in the realm of wildlife identification.

Find a more experienced spotter

Seek others who enjoy nature and are more experienced in identifying species. Wandering with a friend or mentor who can point birds out, who can explain differentiate a swift from a swallow, and who can enthuse you on your journey, helps a lot. It was a big help for me as my interest in wildlife deepened during my teen years, and it’s something I still appreciate as I continue to learn about the natural world.

Online groups can also provide a wealth of knowledge; posting an image, a recording or a description online is often met with very useful feedback from amateur naturalists and wildlife enthusiasts. On the more technological side, we now have apps like Seek that can help identify species by simply taking a picture, saving hours of trawling through ID books. However, I’d not entirely advocate this as a full substitute for the good old ID book!

See what group or species you are more drawn to

As you learn more, I am sure you will feel drawn to a particular group or species that you find captivating; wildflowers, for instance. Focussing on this group or species can really help with stemming the feelings of overwhelming diversity by trying to tackle all the species around you.

Some people may struggle to attune to the wildlife around them, with busy, occupied minds and distractions preventing you from seeing rather than just looking. Pinging smartphones, notifications and long to-do lists that send you worrying about the next meeting or piece of work looming ahead… I’m as guilty as anyone of not being fully present while walking.

Close your eyes and take a moment to settle

In these situations, sometimes it can be helpful to spend a few minutes stationary: close your eyes and listen to all the different sounds around you. Focus on breathing steadily, and then force yourself to really look at what’s around you before you begin to walk. Shifting your headspace into a place of soft fascination that provides an important relief to our overstimulated brains and the areas of our cognition responsible for imagination and creativity. I sometimes switch my phone to airplane mode if distractions are proving too difficult to stem.

And so, equipped with this very rough guide to nature recording, get out on a Slow Ways route near you and see what you can find. Wildlife recording is a never-ending trail of discovery and fascination. With summer now here in glorious abundance and vibrance, there couldn’t be a better time of year to get out and celebrate the diversity of nature emerging from every hedge and heathery hilltop in the landscape.

Enjoy!

FOOT NOTES

Top five identification guides for budding naturalists

- The Collins Bird Guide: The Most Complete Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe (a must-have for anyone interested in birds!)

- Collins Complete Guide – British Wildlife (a brilliant all-round photographic guide to the wildlife of the UK, from insects to birds and plants)

- Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland by Bloomsbury Wildlife Guides (a superb resource for those embarking into the field of moths)

- Plants and Habitats. An Introduction to Common Plants and Their Habitats in Britain and Ireland by Ben Averis (a great plant ID guide and overview of their wider ecology and habitats)

- Britain’s Mammals. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Great Britain and Ireland by WILDGuides (a comprehensive guide to the UK’s mammal species)

Whilst not being a specific book, the Field Study Council (FSC) have an amazing and very useful range of laminated ID guides to all manner of UK flora and fauna, which give a great overview to the main groups without going into the overwhelming detail. Have a look here.

Connecting with other wildlife enthusiasts

- Join the Wildlife Trusts and get out to local events happening near you. The wildlife trusts have a large network of regional groups all across the country, and regularly have different events and volunteering opportunities which provide a great place for meeting other nature enthusiasts!

- Search Facebook for wildlife groups, either local or national, which are a brilliant way of connecting with like-minded people. The Self-isolating Bird Club was an amazing resource during the lockdown period that connected thousands across the UK with the wildlife they were finding in their back gardens and nearby green spaces.

- For younger people, wonderful wildlife groups such as A Focus on Nature and the Cameron Bespolka Trust provide lots of opportunities to connect with each other and carry out brilliant work for nature.

Ben has written for us in the past about tuning into nature, which may be of interest.

If you’ve not signed up for Slow Ways yet, do so here. You can also join the community on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Ben Porter

Ben Porter is an award-winning wildlife photographer, naturalist and researcher from the windswept island of Ynys Enlli in North Wales. His mission is to reveal the beauty of nature and ignite a desire to protect and restore our collective home: Planet Earth.

Since graduating with a degree in Conservation Biology from the University of Exeter in 2018, Ben has spent his time working on projects ranging from landscape restoration in Wales, to seabird research work on far-flung islands, wildlife surveying, freelance photography and guiding. He is particularly passionate about science communication and engaging people with the wonders of the natural world.