Hannah chronicles a failed Slow Ways birthday walk across the Welsh Rhinog mountains in the company of her mum

Good hillwalking, I reckon, requires the right balance of ambition and sense. Ambition to get up there, whatever the there is that you’ve chosen. Sense to make it back again.

Nothing, it turns out, compromises good sense like my last month’s triple whammy of

a) going for a multi-day walk over my birthday which meant burdening it with the weight of occasion;

b) choosing a Slow Way that went through a mountain pass with no alternative options or road access, and

c) tweeting about it, ffs, here and here and here, so there was no doubt about what it was that I was going to fail at when the time came.

And so when the time did come and we did fail, I was really quite proud of myself. The decision to turn back wasn’t as dramatic as it could have been – it wasn’t dusk, I hadn’t trapped an arm under a rock and been forced to saw it off with a spoon. We had bivvies and food and it was June and the pass was much lower than the hills we’d already done. In short, no one is making the movie of how we did battle with Drws Dyffryn Ardudwy, and the mountain won.

But I was proud of us because it would have just been a bit silly to go on, and so we didn’t. And my mum didn’t really want to and we were tired, and the midday sun had come out hot and there was no shelter, and judging by our morning’s mileage we had to concede that we were not a fast-moving outfit, and weren’t about to get faster.

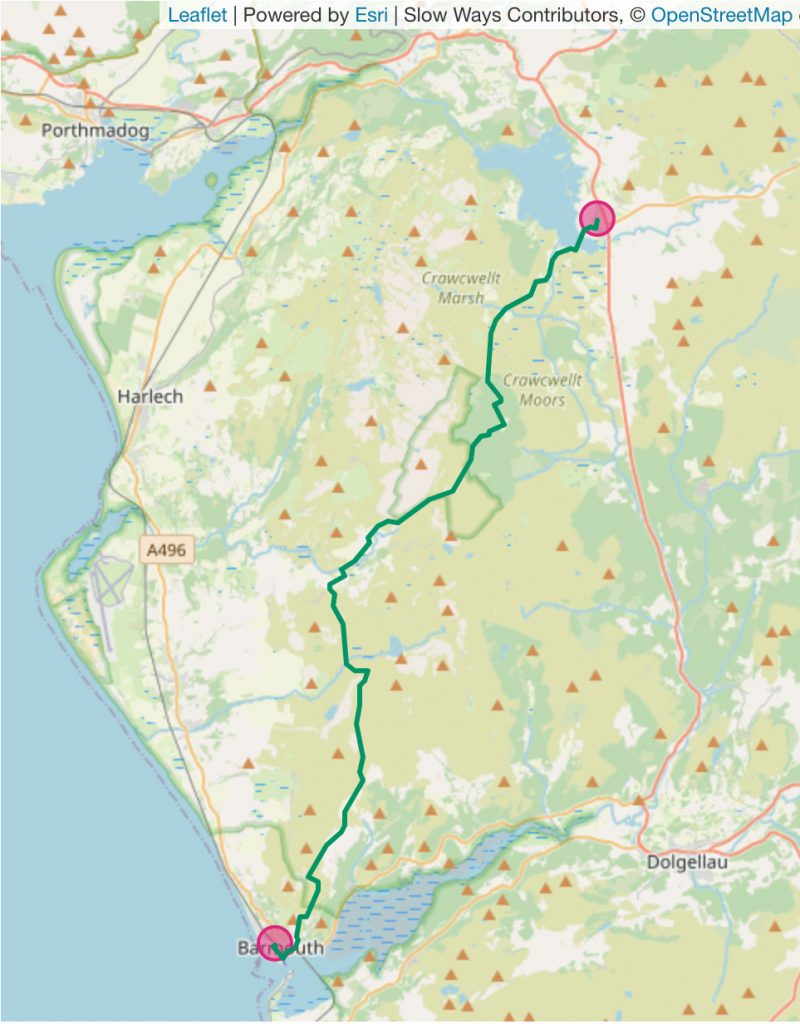

We were walking the un-reviewed Bartra, Barmouth to Trawsfynydd, across the Welsh Rhinog mountains, and all we had to go on was the OS map. I hadn’t done any research into the various parts of the walk, and the remaining 10km was:

* one third mountain pass (probably fine),

* one third forestry (no knowing, but the spruce-drowned ruin in the middle was called Grugle, pronounced Greeg-lehr, meaning heather place, which made me feel sad because it certainly isn’t a heathery homestead any more, and added to the feeling that it could be impenetrable),

* and the last long third a very big bog actually named Gors Crawcwellt – purple moor grass bog – with no tracks or hope-inspiring features, or even a fence, on the OS map. Just the familiar, worryingly straight, green dotted line of a footpath that might very well only exist in theory, law and history.

We’d come across some of these already, one bridleway line of long dashes which took me up the steep shoulder of a hill, across a very high dry stone wall that only Pegasus would have managed, and into a steep hill of ruin debris and ankle-breaking bilberries. The bridleway dashes went abseiling off a scree, and I turned back and followed my mum the way people obviously actually go – the path at the bottom of the hill, with footpath gates and even fingerposts in the real world. I was being too faithful to the map, and to the Slow Way.

I’d been bothered by the destination – the tra in Bartra, Trawsfynydd – since leaving Barmouth. My mum and I are natural derivers (by preference we make it up as we go along), and I was hijacking the first part of her 70-miles-for-her-70th-birthday week to tick off an exciting Slow Way through exciting landscape.

The walk goes up the strikingly beautiful Mawddach estuary, then along some iconic droving trackway, and right between Rhinog Fawr and Rhinog Fach (Big Rhinog and only-really-very-slightly-smaller Rhinog), 18 miles according to the Slow Way listing, but maybe as much as 26 according to mum’s clever map-wheel gadget (see below for more on this discrepancy).

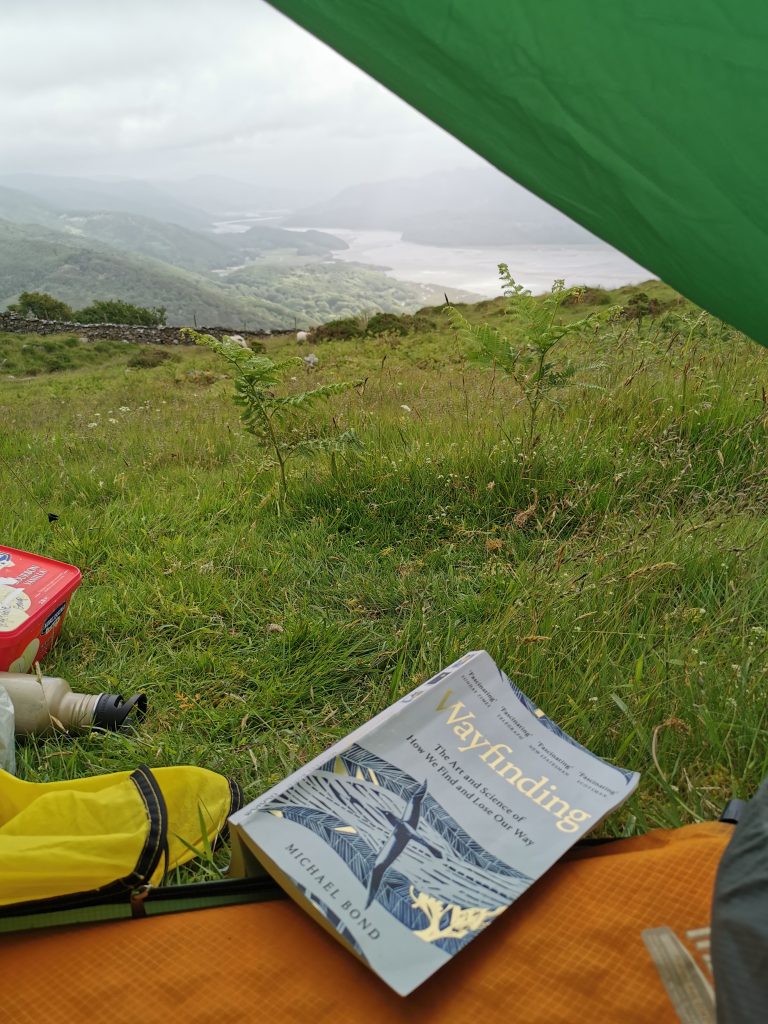

I was made ambitious by the fact that I once could have walked the 26 miles in a day, that it was midsummer, and we had two and a half days for it. I was made cautious by the constant strong wind, mine and mum’s unknown physical condition, and accidentally, on my birthday lie-in in my tent, finally getting to the chapter in my book that was all about horrible stories of people getting lost and dying in their tents whilst hiking*.

The ambition of the walk had made me twitchy throughout, even during my epic birthday lie-in, during the two mugfuls of birthday coffee mum sweetly made me in a billycan on a bracken-stalk fire, and then whilst waiting for the coffee to percolate through our systems so we could pee on the smoking remains rather than inadvertently start an upland wildfire**. I’d been twitchy during the chat with the only person we met that day – a Czech woman who works in a litter-picker-thing factory, doing double our day’s walk in reverse and considering it nothing much. I’d been twitchy across the single field that climbed 300m from one corner to the other, into the thick cloud. Would we make it through the great door of the Ardudwy?

Everywhere our walking labours were belittled by the evidence of labour around us – incredible stretches of dry-stone wall leading off straight up sheer hillsides and along the full length of ridgelines, incorporating boulders where they lay. Giant lintels, huge gateposts, ancient Cambrian rocks dragged about. We slept the second night in the tiny lee of Pont Scethin, a remote 18th century bridge on the Harlech-to-London droving route, along a bronze-age trackway. We had breakfast on the slab parapet where we imagined drovers chewing tobacco to keep alert while the hundred twitchy Welsh Black cattle drank from the stream on the first day of their long walk to market. We were really quite weedy, compared to all the other ghosts around here.

Still, despite all the shame, we gave up and I turned downriver, away from the pass, leaving mum happily washing her clothes and boiling her billy in a clearing by Nant Col. With gravity on my side, plus the levity of junking the anxiety of getting to Trawsfynydd, I rattled on down to the sea. I got the train up the coast, and a taxi round the north edge of the Rhinog range, and to the parked van, with a mirror-image view of the moody pass from the other side. We’ll be back.

I’ll do things a bit differently next time.

Tips on pioneering upland or remote Slow Ways

1. Leave more time than you think

Slow Ways is in a pioneering phase. The routes have been created by people who sometimes don’t have on-the-ground knowledge, and the only way they can be checked is to walk them, which is exactly what is going on all over GB, at a tremendous rate, day after day (thank you!). But checking is time-consuming – going round blocked routes, overgrown bits, mudbaths, with no guarantees.

It may be particularly important to know when you’ll arrive at your destination – for catching a train, crossing a causeway, not being benighted on a hillside, or meeting your sweetheart for a romantic meal. If you’ve got an inflexible deadline you might want to budget up to twice the time you’d need to walk a route you know, or that has good signage. The longer the walk, the longer the ratio of extra time you need to set aside.

In addition, the gpx routes sometimes cut corners a little, and these can add up over the length of a walk.

2. Plan for failure

Do give it a little thought before you head out – what will you do if you don’t make the train, causeway, mountain pass? Study the route in advance and see if there are alternatives available to you. If you can’t go through a mountain pass perhaps there is a route around the base of the mountain to the same place? Does the path meet up with a B-road, farm track, forestry road or named trail that might offer you a get-out.

3. Don’t be like Hannah; do research in advance

If you are walking through a number of unknowns, like my mountain pass followed by forestry followed by bog, do a bit of a search online in advance. As soon as I gave up and got back to mobile reception I discovered that there was a pdf online of marked and established leisure walks around the forestry section. If I’d known this at the mouth of the pass I’d have felt a lot more confident to go onwards.

In retrospect I think I was excited by the adventurous blank slate of heading up with only a Slow Ways route to follow (and I personally quite like the chance encounters and awkward freedom that happens when plans are scuppered!) But maybe if I park on the other side of a mountain again I’ll do a little tiny bit of research; I can’t afford taxi rides with every walk.

4. Take a compass, OS map etc – certainly don’t expect any path on the ground

Take everything you need to be safe. If the path doesn’t exist on the ground, and the cloud comes in, or you navigate by an app on your phone but drop it in a mountain stream or navigate by OS map but it blows off a ridge in a gale… make sure you have methods enough to know where you are and where you’re going. That Slow Ways route-line can inspire false confidence – remember, remember, we’re in a pioneering phase!

5. Concentrate!

Tim Ryan reviewed the Llanddeusant–Ystradfellte route in the west of the Brecon Beacons (whole story here):

“Crossing the Black Mountain I thought, I’m really having to concentrate here! I’m in perfect clear visibility, navigating with a map and compass – it was a classic mountain leaders’ qualification environment. Spotting every rocky outcrop, knowing exactly where I was at all times; it was really tricky. I’ll have to advise in the review that this is only undertaken with a map and compass.”

5. … or walk one that’s been reviewed

We are on the way to getting a fully verified network, which means at least three positive reviews for each route. If you don’t quite have the time, the map and compass, or the energy to pioneer a route, find one that has a review or two and help get it towards verification. Knowing that someone else has walked it recently, and making use of the tips in their review, can be much more relaxing, and we need you just as much!

Remember though, you may not agree with their positive review, so do still take the safety steps above!

6. Consider the OS app and check weather forecasts

Naturalist Ben Porter (the man behind this gorgeous piece – sound on!):

“One of the resources I’m finding super useful at the moment is OS maps on my phone, which is really helpful in assessing the existence of paths and cross-referencing your journey with that outlined by Slow Ways. You can actually upload the gpx from Slow Ways into OS maps, and follow it/look at it in their app then. Otherwise the good old-fashioned paper version is a must-have for anyone heading to more remote areas.

“I’d also add that checking a weather forecast is a very good idea – MetOffice is best for the uplands and mountains, and this should be factored in if it’s going to be misty etc.”

7. Be observant

Super-long-distance walker Ursula Martin (eyes peeled for a story from her coming soon) advises: “Try to notice whether you’re on open access land where you can walk anywhere, or normal agricultural land where you can’t – the open access land is beige on the OS map.”

She also points out that quite often the path is there somewhere, running alongside you while you bluster through undergrowth. Sometimes it’s good just to take a few minutes to look around and try to read the landscape.

“If all else fails, take a tip from Tristan Gooley, the Natural Navigator, and look around you. The sun, the weather, the trees – all of these hold clues to the direction, which could help you get your bearings.”

*Wayfinding: The Art and Science of How We Find and Lose Our Way by Michael Bond. It’s a brilliant book, I enthusiastically recommend it and will review it here soon. The author spurs you on through many chapters of fascinating neurology with the promise of these grizzly true-life stories. I’d been reading the book for six months (I’m currently as slow a reader as I am a walker, blame early parenthood) and it was bad luck that I’d reached that chapter while easily spooked on a hillside.

**This walk happened in mid-June, when the land was well-watered, as you can see. I just want you to know we’d certainly not be lighting a fire right now, in this mid-August national tinderbox.