An unsettling walk along the fastest-eroding coastline in Europe, marking the anniversary of the Great North Flood – our biggest peacetime loss of life

Slow Ways story contributor, community artist and founder of Under Open Sky, Genevieve Rudd, embarks on a journey from her hometown Gorleston-on-Sea to Lowestoft, East Anglia.

Along the way, she reflects on the context of her community work, the Great North Sea Flood and the alarming realities of climate change. Genevieve creates painterly photographic drawings inspired by the walk, using collected sand and sea water.

“On the night of 31st January/1st February 1953, the coastlines of the UK, the Netherlands and Belgium were impacted by the Great North Sea Flood, our biggest peacetime disaster and loss of life in the 20th century.

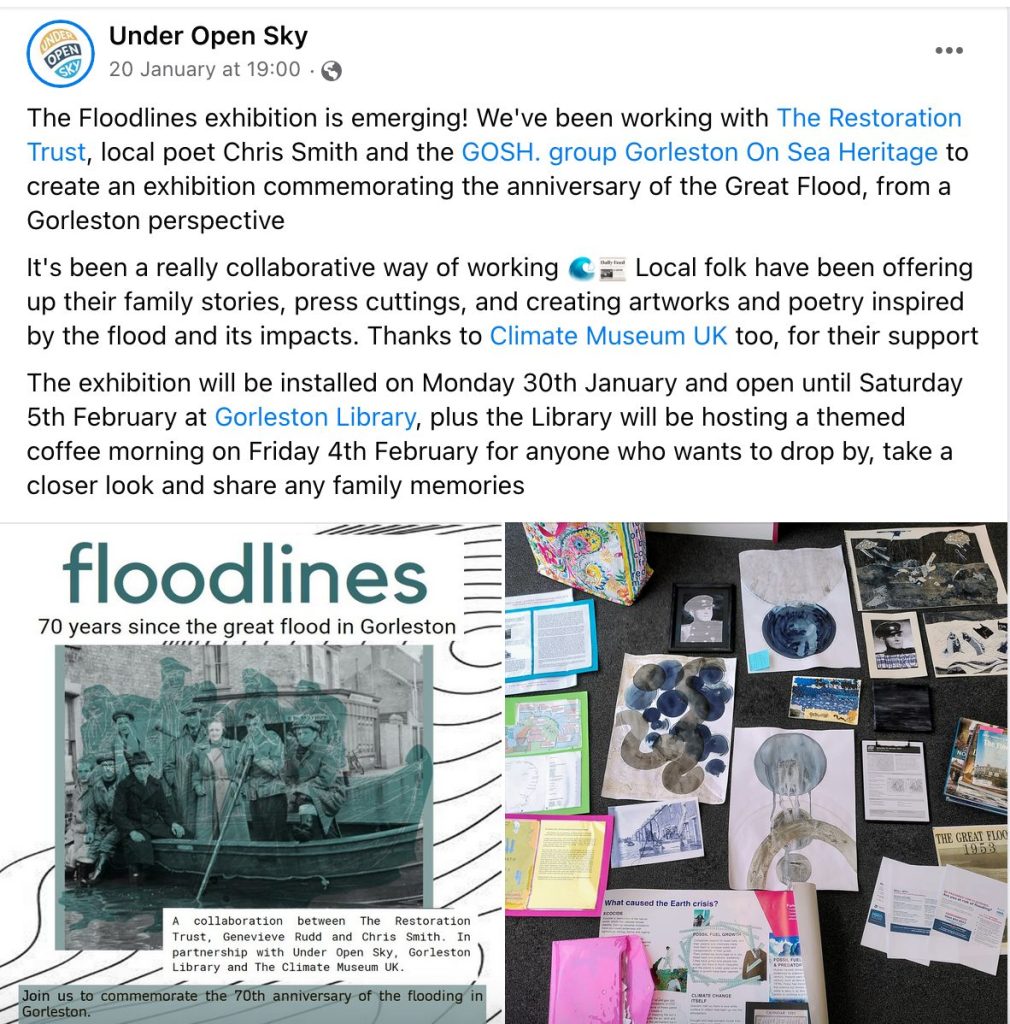

I’ve been exploring this experience at Under Open Sky, during a collaborative exhibition project with The Restoration Trust mental health and heritage organisation, Gorleston-on-Sea Heritage Group and Gorleston Library. On the anniversary week, we’re hosting the Floodlines exhibition at the library, with support from Climate Museum UK, which I’m also an associate of.

For my Slow Ways walk in late January, I chose a route going down the coast – from north to south, Norfolk to Suffolk – as the wind did on the night of the flood.

I left home on the day of my Slow Ways route feeling unsettled. The new year has blown into my life in a cloud of busyness, with short-term deadlines and low capacity to think. When I was invited to be a story contributor for Slow Ways I was incredibly grateful, as it felt like being gifted time and space for my arts practice. My plan is to use this time to take an idea for a walk, gather up concepts or thoughts that have emerged from my arts practice in that season, and walk with them to embody or evolve the story, to deepen into their message or find new layers.

I have an environmental arts practice that runs as an undercurrent to my community arts work, which includes being the founder/director of Under Open Sky, a coastal engagement organisation based in Great Yarmouth on the Norfolk coast. It’s for these reasons, and more, that I wanted to focus my first Slow Ways story on my local coastal patch, from Gorleston-on-sea in Norfolk to Lowestoft in Suffolk, a seven-mile stretch. In my work with people, and in my own arts practice, I explore climate, nature-connection and environmental engagement through arts and walking, often with a health and wellbeing focus.

For my Slow Ways walk in late January, I chose a route going down the coast – from north to south, Norfolk to Suffolk – as the wind did on the night of the flood

It was a cold morning when I set off and the air was heavy with a near-rain, wet enough to damp the clothing, but not hard enough to warrant an umbrella. It was one of those heavy, flat days, which felt like a mirror to my internal landscape. The Gorlow route starts a short distance from my house in Gorleston-on-sea at Marine Parade, the upper promenade looking down towards the sea and the shops, amusements, yacht pond and car park below. As I walked along the prom, I thought, ‘why didn’t I wear a hat?’. Already, my head was cold and I looked down at the route map on my phone and wondered whether seven miles was a stupid idea when I’d forgotten to check the weather forecast.

Why didn’t I wear a hat?

I was glad to drop down to the lower level of the promenade, to duck out of the wind. On the descent down the steps, a passerby remarked, ‘I thought it was going to be brightening up this morning!’. Reaching the end of the concrete path, under the flat grey sky, I checked my phone map. The next part of the route was to be on the sand, between the wooden sea defence wall of groynes and the crumbling cliff. Despite being a born‘n’bred Gorlestonian, I don’t think I’d ever walked right down to the end, but I was open to being guided by the Gorlow route.

Lapping water was pushing and retreating from the sea defences, causing gurgling and squelching noises like bubbling lava. The constant to and fro of the water was layered up with the repetition of my footsteps pushing into sand and stones, and the squawk of the gulls overhead. I was grateful for the time to be alone and soon forgot about my cold head.

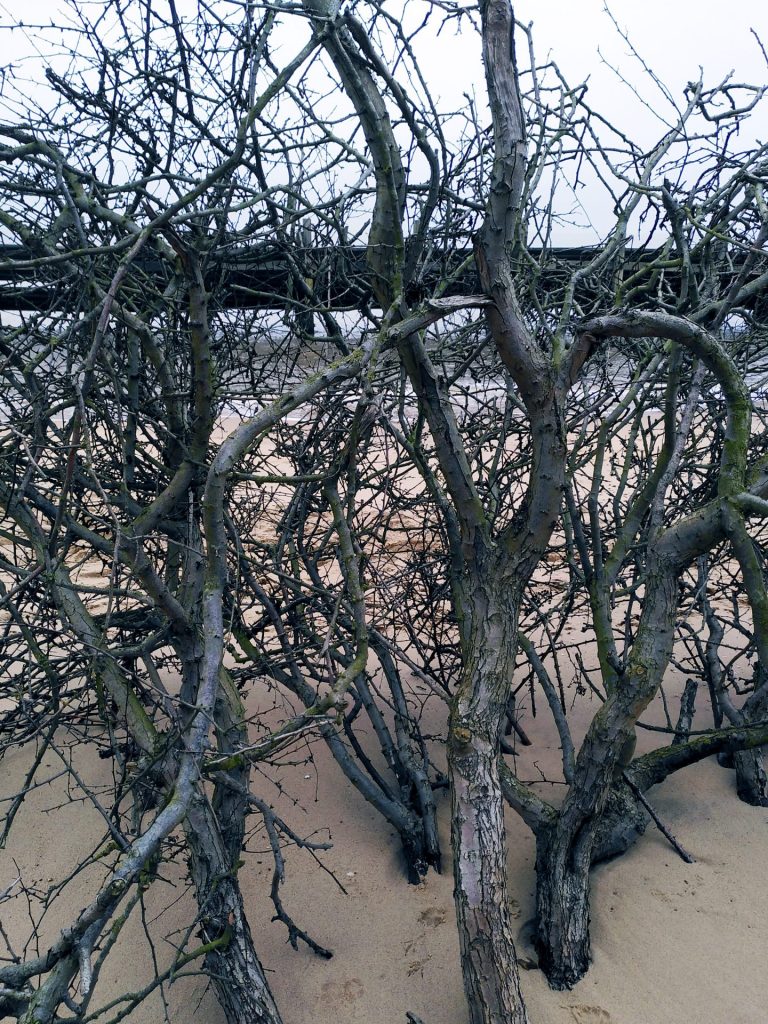

Walking between the wooden structures, keeping the sea at bay to my left and the collapsing cliff to my right, was difficult at times. I felt safer walking straight down the middle, being alert to the sea coming in too close or the cliff falling down on me; fortunately neither happened!

Unsure footing

I noticed that there were dense numbers of footprints – human, animal and bird – in the sand, so I assumed that, unless a tourist load of people had been visiting this isolated stretch earlier that morning, then I would be safe as the tide didn’t come up quite that far – yet.

I’d already eaten my snacks before I’d technically left Gorleston. I wanted something to carry a handful of orange pigmented sand in, which had earlier fallen from the cliff edge above. Amber sand wedges had fallen in piles against the lighter beach sand and, as I crouched down to collect a handful, I looked up at the stratum looming over me and exposing its underbelly to the sea. Every so often, the path and ruined cliff was dotted with remains of trees and shrubs, weathered back to grey carbon. In the distance, like a mirage, I noticed a set of metal solid steps and felt reassured by its promise of a solid surface.

The metal steps led to a crossroads: either following the route indicated on the map which was, in places, less than one metre away from falling into the sea, or taking a tree-lined path going inland. On choosing the latter, I spotted two figures ahead in red coats. As we met in the middle of the path, I asked whether they’d come from Gorleston as I thought I’d spotted the pair whilst I was using the public facilities at the start of the route, on advice from a previous Slow Ways reviewer.

Bear witness to the crumbling

When they said they were staying at Pontins, I smiled at their red (rain) coats. I asked about the next stage of the route, and they advised cutting through the golf course and caravan parks whilst heading to Hopton, as the cliff edge was rapidly falling away, so much so that the beach was now closed. This stretch of coast is one of the fastest eroding in Europe and walking this route was a stark reminder of this immediacy. Later that day, the local paper featured a public consultation about the erosion impact on communities. Walking this route was difficult and unsettling, but necessary, to be a witness. As I left the red coats, I remarked that, ‘if you can do it in January, you can do it anytime!’, as much to chivvy myself along as to reply to their surprise at the long route I was taking.

This stretch of coast is one of the fastest eroding in Europe and walking this route was a stark reminder of this immediacy

Hopton-on-Sea was living up to its name; the seawards edge felt sharp and stark. The coastal defences looked like stitches in the water. Much of this part of the route was unreachable, so I followed the redirected signs inland pointing to the ‘Alternative Coast Path’, through the caravans and fields. As I moved away from the sea, the sounds changed. The whooshing of the wind and sea was replaced by speeding cars and vans on the A47 across the ploughed land. I was unsure, again, what the next turn would be.

Would it exist, if or when?

Unsure whether if or when I revisited this path again, would it exist? How far inland will the path travel on its Alternative Route? Or will we need to adapt further, beyond retreating and defending, like the Moken people of East Asia? These communities have learned to travel further into deeper waters for safety when the seas rise, like the dolphins do, as they have kept alive their water wisdom.

As I entered Corton, the smell of the pollution from the passing cars and vans struck me. It wasn’t busy with traffic by any means, but on a cloud-thick day like this one, the toxins hung in the air. Whilst there are permanent homes through the village and signs of everyday life, signalled by dog walkers, the would-be sea view from the road I walked was compacted from caravan parks. Ocean Glade and Azure Seas: are they looking at the same view as I am? Erosion Umber and Whiteout Fog would be more fitting.

Woodland trees and icy ditches lined the road and, as the smell of wood smoke started to drift in the air, I noticed I was on the Waveney Way. The Waveney river, like my walking path, weaves together the Norfolk and Suffolk boundary when it enters from the North Sea. Ankle-height Alexanders brushed against me, poking through copper bracken and discarded litter. These punchy green plants were brought over by the Romans, which felt fitting, as I kept a steady pace along the straight road towards Lowestoft.

Grey on grey makes me aware of my feet

Turning off from the Corton Road, the sea was visible again, a faintly distinguishable line between sky and sea shrouded in fog. The walk into Lowestoft on the concrete sea defences felt so different to the Gorleston stretch. At the early stage of the journey, the coastal edge was crumbly and elemental, the soundscape was gurgling water and birds wrapped around me. This concrete embankment around the Lowestoft coast is protecting homes, businesses and industry, and on the day I was walking, the palette of grey on grey made me aware of my feet starting to rub. I thought the Gorlow route would take me past Ness Point, the most easterly point in the UK at Lowestoft, but instead it weaves back inland through the industrial estate before meeting the A47.

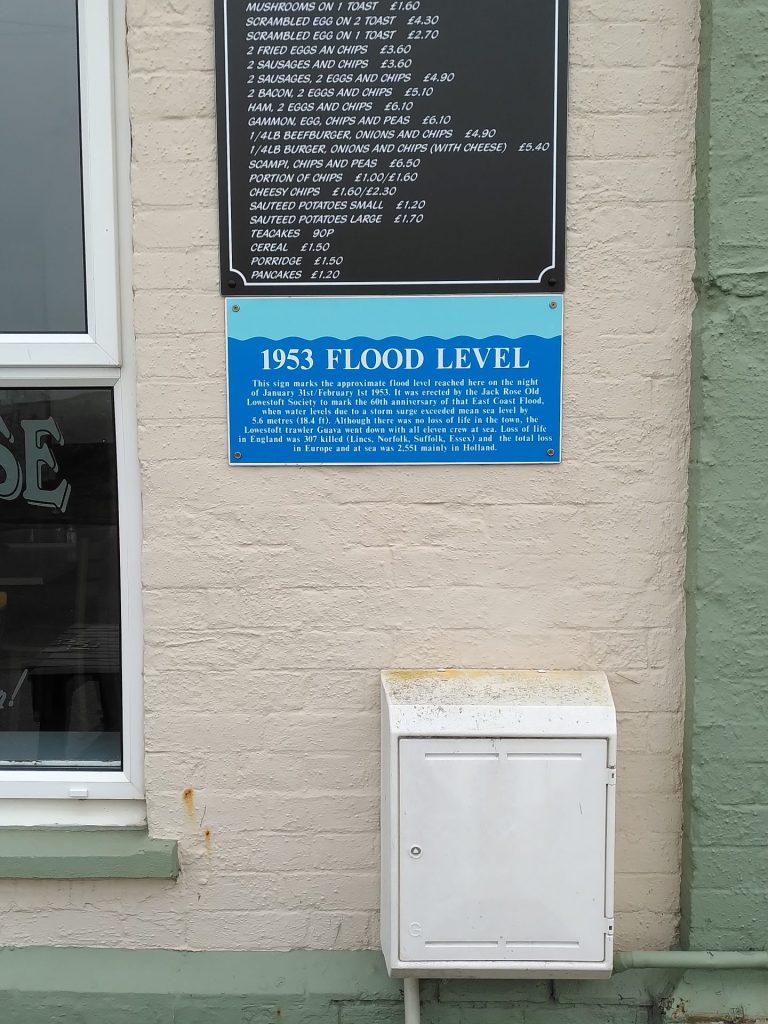

As I pass factories, puffing more clouds into the clogged atmosphere and the largest wind turbine smothered in a wispy haze, I notice a sign commemorating the 1953 Great Flood, and another one further along the street, weathered and crackled. I’m reminded of my starting point as I head towards the end. When I’ve been researching stories of the Great Flood it was the lack of communications that is cited as the cause of so much damage. The responses were led by communities, much like the mutual aid networks during covid lockdowns more recently.

We have more means of communication as a planet than we’ve ever had, and the message of coastal danger – the eroding cliffs, the rising seas – still feel like they’re being unheard

Looking back from today’s vantage point, as I’m guided with GPS using the Ordnance Survey map on my phone to follow this Slow Ways route, it’s hard to imagine being without this constant access to communication. And yet, we have more means of communication as a planet than we’ve ever had, and the message of coastal danger – the eroding cliffs, the rising seas – still feel like they’re being unheard. I was aware of my solo physical occupation of the space, as the only human in sight for most of my journey by the sea, but always being reminded of humanness along the route: as witness to human-made coastal change, weakened and weathered sea defences, holidaying along the edge and roads cutting through the landscape.

Within three hours of starting the walk from Gorleston-on-Sea, I had reached Lowestoft. The Slow Ways Gorlow path ends the route just outside the station. I took a moment to celebrate, to myself, for completing the walk. As I made my way back into town and on the bus, I passed right by the walking routes I’d just covered.

My hands and face felt tingly on the bus from the cold wind. I slumped into my seat and wrote notes, as I wooshed past the most easterly point, the detour field, the caravan parks, the undefended sea and back towards the start. As I went across my journey at speed, running parallel to the cliff edge, I wondered about the future of this edgeland. Edges and boundaries feel so final, so defined.

The walk reminded me of what disturbs me most about the earth crisis is that the baseline of our existence – clean air and waters, habitable lands – is crumbling away.

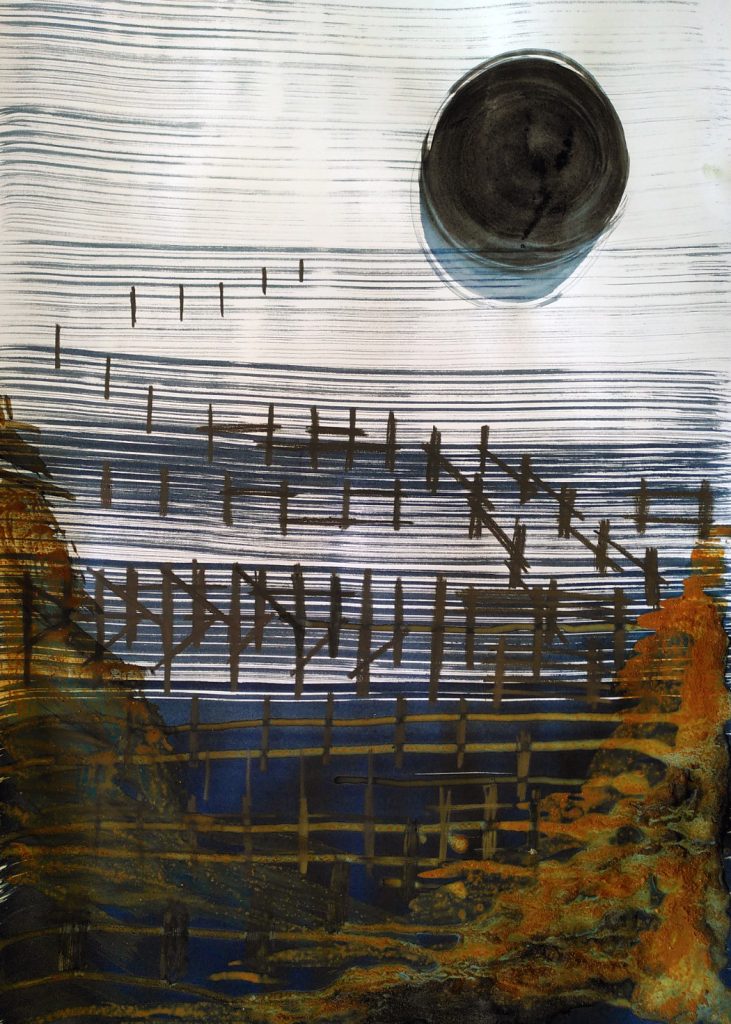

Using a small amount of orange pigmented sand collected from Gorleston and some North Sea water, I’ve been creating photographic paintings inspired by the walk along the eroding coastal edge. I’m working on an ongoing series, Earth Light Paintings, using gathered natural materials and photographic chemicals. This has so far included beach-combed chalk, industrial riverbank mud, rain water and soil. In this series, I’m processing edges, boundaries and tipping points, and what it means to be alive to witness climate breakdown.

Using a small amount of orange pigmented sand collected from Gorleston and some North Sea water, I’ve been creating photographic paintings inspired by the walk along the eroding coastal edge

As Stacey McKenna-Seed recently said, “walking makes us switch from the sympathetic to the parasympathetic nervous system, which triggers the creative side of the brain”. I feel moved by the sight of the cliffs, sea and birds, walking along the coastal edgelands on the Norfolk/Suffolk border, and the triptych captures my observations and sensations. The future of this coastline is rapidly changing, before our very eyes, and it feels important to be physically, emotionally and creatively present with this change.

Earth Light Paintings – Slow Ways Gorlow one – January 2023. Three painterly photographic drawings made using cyanotype photographic chemical Indian ink, graphite stick, collected sand and North Sea water (420 x 594 mm)

Genevieve Rudd

Genevieve Rudd is an experienced community artist based in/from Great Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast. She develops creative projects that encourage closer looking, and that ask about the places and people around us. These include environmental arts, working outdoors, walking and nurturing nature-connection through creativity. Genevieve’s participatory work with people often explores the intersection between arts, health & wellbeing, and climate & environment. In her own arts practice, she considers themes of time, place and seasonality through slow photographic practices. This includes growing plants to use in her work, capturing seasonal moments and weather events, and creating artwork that can compost back to the earth. Genevieve is a qualified Wild Beach Leader and Founder of Under Open Sky, a not-for-profit organisation exploring our relationships to the changing coastal climate through multidisciplinary approaches, based in East Anglia.