As part of Refugee Week, Saira joined Dima Aktaa, an amputee, runner and aspiring interior designer, on a Slow Ways journey from her home in Flitwick to Amthill

I met Dima at her home in Flitwick, a small town in rural Bedfordshire where she has lived for five years. She arrived from Syria with her mother, sisters, and brother as part of a UN resettlement programme. Dima lost her leg when a bomb hit her family home in Idlib in 2012 during the war in Syria.

During my walk with Dima, I found out about her journey towards getting a prosthetic leg, her motivation behind running a half marathon, finding home in Bedfordshire and what walking offers her.

Setting off from Flitwick

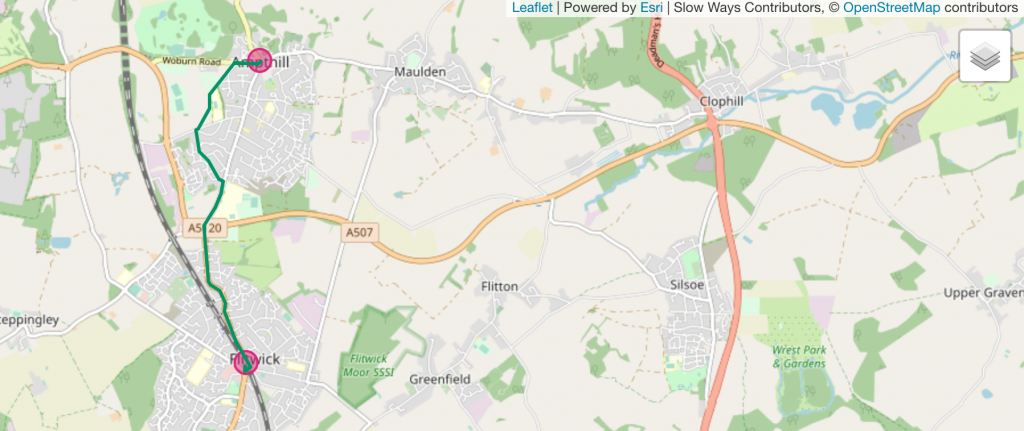

We initially planned to walk to Flitwick to Woburn Sands, but as it was a very hot day, we decided on a shorter walk to Ampthill instead. Shortly after we arrived at the centre of Flitwick, we had lunch at Costa where I got to know Dima a little. We spoke about our lives. We spoke about walking. I asked her why she walked. It was a loaded question, but it felt like a fitting entry point.

She told me she was in Kings Cross last week after training. She felt a heaviness. She knew she couldn’t go home; she couldn’t carry those feelings with her. So she decided to walk. She walked with no destination in mind and arrived some time later at Big Ben, feeling lighter. She sat on a bench in the sun and watched people. She said that walking would take her out of her head. She would be reminded that there were other people in the world, and that they had their own problems too.

She told me that as she was sat on the bench, a young man approached her and asked if he could sit down next to her; she said yes. He told her that her eyes were beautiful in the light. She thanked him. She told me these interactions filled her with joy – kind words and smiles; walking allowed for them.

After lunch, we started our walk to Ampthill. The route was straightforward and varied. We wandered down a busy road before turning in and following quiet flower-shrouded paths in residential areas. Dima stopped every now and again to smell the roses.

We spoke as though we were old friends, sharing stories as we went. Our conversations were broken by the odd hello or a brief exchange with a passerby. Dima shared her experiences, her hopes and aspirations – to run again, to make a difference to people’s lives and to become an interior designer. She would be starting university in September. I was taken by her authenticity, sense of self and her unwavering gratitude to God for life.

As we arrived at Coopers Hill, a local nature reserve, we sat under a tree. An insect crawled up Dima’s prosthetic leg; she spoke to it and took a photograph. I pressed the record button on my phone and we began to have a more intentional chat.

Where did you walk in Syria?

I knew Dima walked and ran often before the war. I’d visited Syria myself before the war, in 2008. I was struck by how beautiful, varied and wondrous the country was – I’d walked in the souks (bustling, colourful, fragrant markets), by the mountains dotted with tea shops that surrounded Damascus, and in the folds of the old city of Aleppo. I remembered passing through open plains filled with olive trees and small green villages. I wanted to know where Dima walked.

Dima told me she walked in Idlib to her school every day. She would take part in running activities with her classmates.

She liked walking by the sea in Latakia, an ancient port city, known for its beautiful beaches and crumbling castles. “We’d go every year and stay for three months during the summer holidays. No one sleeps in Latakia, we’d walk by the beach every night.”

Dima said she also used to do a lot of walking in her city Idlib.

“When the war started, we carried on living as we were in Idlib, but it was more dangerous. If you were going to Aleppo you didn’t know if you’d return. And then we couldn’t leave. We had to stay home. We struggled to find food. We couldn’t travel outside the city. In 2012 the bomb hit my house. It came suddenly out of nowhere. My family was at home. Luckily, I was the only one hurt. I was grateful that everyone else was ok. It was a miracle. I lost my leg straight away. It took two hours to get to the hospital; from the backseat of the car I could see bombs falling like rain over the city. It was so scary. I thought, the bomb didn’t kill me but I will die on my way to the hospital. My mum and cousin were in the car too.”

A new start

After five years of using crutches Dima came to the UK where she got a prosthetic and learnt to walk again. “Back when I had my accident I was still the same person, but people couldn’t see that. They would say ‘poor girl’. When I got the prosthetic I felt so excited. I was happy to learn to walk again.”

“I love my life, to be honest! I got a prosthetic leg, I’m learning how to use it. If I had two legs, my life would be so boring! I’d never feel the joy of learning how to walk again”

But more than that Dima wanted to run. “I wanted to run again, but for a purpose; I wanted to raise money to help young Syrians to get prosthetics. I didn’t tell my doctor. I ran a half marathon. My coach didn’t stop me, but he told me it would be hard. It was so difficult, but I had a reason for doing it and that kept me going.

“Children can’t describe how they feel. I know the pain and all the feelings that come with losing a part of you. It was really tough. When I reached the finish line, I was overwhelmed – I wanted to laugh and cry at the same time. I felt joy and sadness. I was doing it for children who were going through the same thing I went through. It gives you the power, and purpose.”

Later on Dima told me she recently had another accident. “I just recovered from my leg surgery and got my prosthetic. And then I cut my hand; the blade fell off and went through very deep. My doctor said I needed surgery or I would lose the nerves in my hands and my ability to move my hand. I couldn’t believe it. I began to laugh. I felt so sad. It would set my training back again. Every time I have a problem, I try to fix it. If I can’t, I move on to the next problem. God doesn’t test you with more than you can handle. I say Alhamdulillah, ‘praise be to God’ always.”

Who do you walk with?

“My mum, she’s my best friend. She often watches me train. We walk from Flitwick to a village close by where my mum has an allotment.”

Tell me about Flitwick

“I like it here. People are so friendly. It’s so calm. You have time by yourself. I’m not a London girl. I love the countryside; I don’t like cities or towns. First time I came here, from Heathrow with the charity, they dropped us. I said to myself whatever it is we’ll accept it. When I came from the car to house, I said thanks God, we have a roof over our heads. I feel safe. It’s quiet, nice, and peaceful. People smile at you.”

Arriving in Ampthill

I thanked Dima and stopped recording. We sat for a bit longer before we made our way to Ampthill which was now only a short walk away. Ampthill was picturesque, with great big houses and perfectly pruned hedges, a handsome clock tower, quaint shop-fronts and bunting left over from the Queen’s Jubilee.

We bought cold drinks from Waitrose and sat at the bus stop. The bus was due to arrive in 32 minutes. In that time, another young lady joined us and we began talking. Her name was Tanya and she was a Ukrainian refugee who had only been in Ampthill for a few weeks. She told us home was no longer safe. We sat next to each other on the bus when it finally arrived and Dima shared her local knowledge. As the bus chugged along, she pointed out the public library, the local shops and green spaces; she told Tanya where to get off the bus to get to the train station. When Tanya got off Dima told me wistfully that she reminded her of herself when she first arrived in the area. Their brief interaction was filled with warmth, mutual understanding, a knowing silence. To find home in unlikely places and with unlikely people is something I’ve long been accustomed to, but I would never know what it felt like to do it in exile.

Saying goodbye

Dima and I missed our stop on the bus. I could sense Dima was tired. She told me earlier that heat caused her prosthetic to rub painfully against the stub of her leg. I called a taxi, and we went back to her house. Her mum brought us some fruit and I took photos of Dima with Lily her kitten before wishing them goodbye and promising to return one day.

I took a detour back to the station and walked across an empty field at the edge of the road, surrounded by the Buckinghamshire countryside. I thought about the day and how much I had learnt in the way of gratitude, resilience, and positivity during our time together. It felt rich and expansive, I’d discovered two new towns in a part of the UK I barely knew, and more importantly I made a new soul friend. Someone who had turned something terrible that happened to them into an opportunity to live more fully.

My Slow Ways journey also got me thinking about walking in a different way. I thought about the students from minoritised backgrounds in Ukraine who were refused access onto trains and were forced to walk out of the country. I thought about friends of mine who happen to be refugees; kind-hearted, selfless individuals who a decade earlier had largely walked to the UK from war-torn countries like Syria. Their journeys were arduous, emotionally, and physically. They walked out of necessity and for survival, pushed forward by the hope that where they arrived would be better than where they came from. They walked until they could walk no further, until they arrived at the Calais Jungle. Until they hit the sea. Those friends still associate walking with trauma. I thought about my privilege, to walk mostly for joy, for connection, for understanding – to seek out hidden spaces and stories, and to find hope and home in unlikely spaces. To take the Slow Way…

I’m also reminded of all that can come from walking: space to reflect, time to nurture relationships with people, nature and places, creating memory, and imagining where new and better paths (in every sense) would help.

Follow Dima on Instagram and have a look below for a music video by Anne-Marie on her recovery. #SlowWaysJourneys