Queer eco-poet, Caleb Parkin and his terriers, the Scruffs, explore the beauty of the Wye Valley, the eye-popping background to Netflix’s utopian teenage series, Sex Education

One of the things I enjoyed about the Netflix series Sex Education (2019 – present) is the way it transformed the landscape of the Wye Valley and Forest of Dean. The backdrop for the show’s stories of gender, sexuality and identity is this forested valley idealised and remixed, its river and bridges the locations for snogs, breakups and sassy one-liners.

I suspect, despite the teenage characters, I’m more the show’s demographic — 30s/40s, often queer; of those who recall a schooling without any of these frank, enlightened conversations about the nuts, bolts and emotional nuances of adolescence.

Instead, we had Section 28, which only concluded in 2003 (with a much longer shadow). It was an era of censorship, shame and a total lack of ‘sex education’ for anyone deemed “abnormal” or who might have tended towards the “pretended family relationship” of a same-sex partnership (in the words of Section 28 itself).

My intention here is to write something pop culture-infused about both this natural landscape and also how the ‘landscape’ has changed for LGBT+ young people to be “out in nature” (groan)

With no buses out this way and two dogs in the boot, I headed over via the M4 diversion and passed Chepstow racecourse en route. My intention here is to write something pop culture-infused about both this natural landscape and also how the ‘landscape’ has changed for LGBT+ young people to be “out in nature” (groan).

But this morning, I read yet another article evidencing what we humans are doing to our fellow earthlings; human biomass, combined with all our livestock, vastly, literally outweigh all wild mammals. Even the immense whales, in their dwindled numbers, can’t compete with the unstoppable bulk of humankind, our canine companions, our Chepstow racehorses.

Who cares whether we can hold hands in public or if the outdoors is a truly genderful, inclusive space, when we are all just a big lump of humanity, flinging wildlife into space on the planet’s biomass seesaw?

I’m here now though. There are bridges to look at, including the one where Adam got dumped by Eric (rightly so, in my opinion), and I might get lunch at Browns Village Store. Maybe being “out in nature” will help me forget the news for a moment, of how much nature is out; that is, gone entirely. Maybe being out in it, trying to imagine that it could possibly become itself again, is the point?

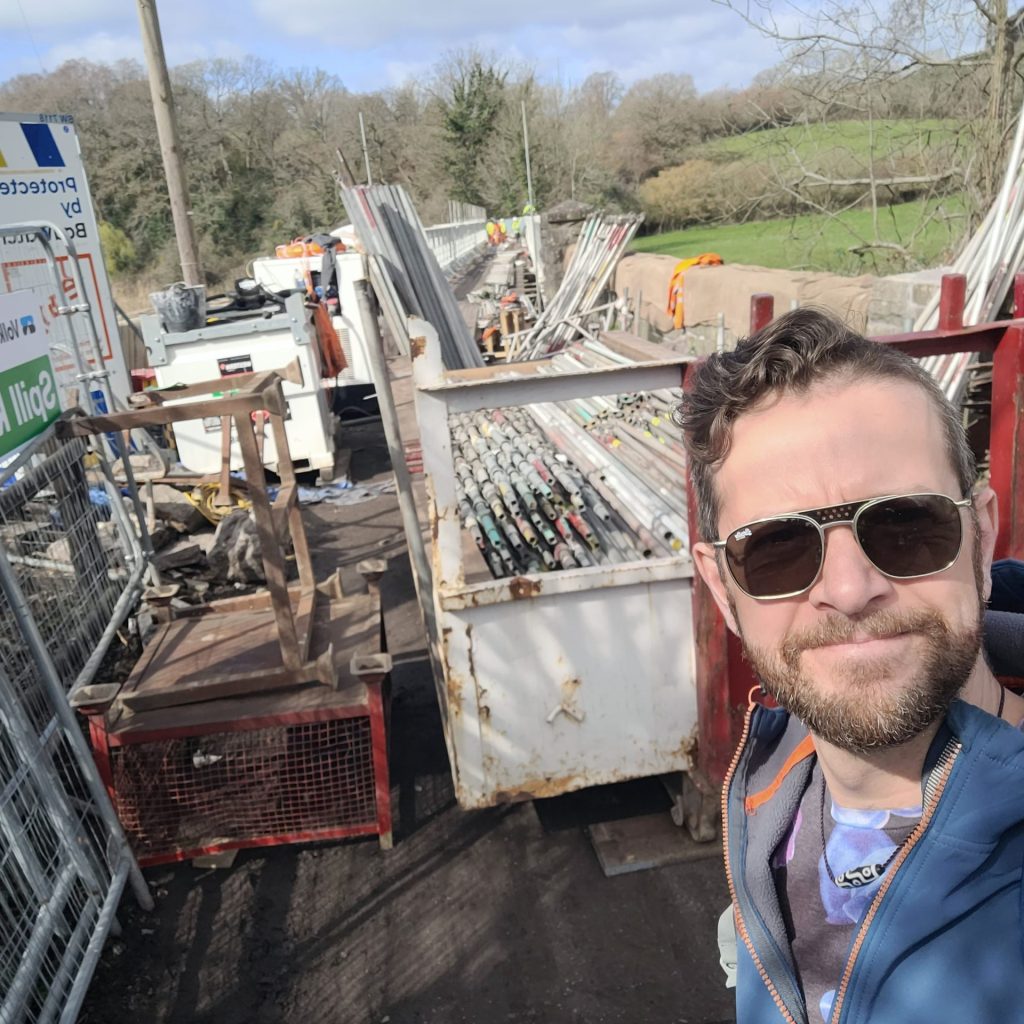

Wireworks Bridge

Wireworks Bridge is closed for repairs. I wonder how many others have come, as I have, to see this site of many a pithy and dramatic exchange, before characters whizz off on bikes, turning a corner to a location which is, in reality, 20 miles away.

I suspect more tourism isn’t really required at Tintern Abbey but wonder whether the money from all the Sex Education tourists is contributing to the repairs of this industrial heritage. I hope so.

A while back I read a Granta piece, Shifting Baselines, about biodiversity and abundance or lack thereof, in the perception of each consecutive generation. We don’t know what’s missing if we haven’t grown up with it.

There’s a football match on the playing fields, men and boys in high-vis roaring at each other. More men in high-vis clank across Wireworks Bridge, as they piece it back together.

Sometimes I feel all-too high visibility myself, with some rainbow socks or nail varnish on. What remains visible? Who or what becomes invisible, simply in their abundance?

Brockweir Bridge

It’s definitely a spring day. On my way to Brockweir Bridge, I’ve been thinking about utopias, non-places. How this valley became one, on-screen.

The thing about utopias is, what gets edited out? Sex Education‘s Wye Valley is transatlantic, post-racial, delightfully queer. There’s no dog poo in gutters, no front lawn flags for ongoing conflicts abroad. Instead, it’s a valley of snappily dressed, glittery beings on charming voyages of discovery.

I’m relieved to find the footpath again after the narrow pavements. I think about how different it is to follow meanders rather than tarmac.

Sex Education‘s Wye Valley is transatlantic, post-racial, delightfully queer

I pause to identify a particular, persistent birdsong. It is a tit, of some sort. The BirdNet app says it’s a great tit, with a background of rooks. How perfect, I think, this Carry On vibe— out in nature searching “great tits” online. How ideal, with that gothy backdrop of rook.

We’re on the other side of the Wye now, then over at Bigsweir, back down via Llandogo and Bargain Wood; all are filming locations.

It’s almost certain I’ll need another ‘nature wee’ on the way (yes, I’ve already done one). Hopefully there’ll be a quiet spot to be “out in nature”, adding more fluid to the riverscape. Hopefully I won’t get caught or caught out, but manage to find an off-path corner (utopias definitely have public toilets, just not AONB riverbanks.)

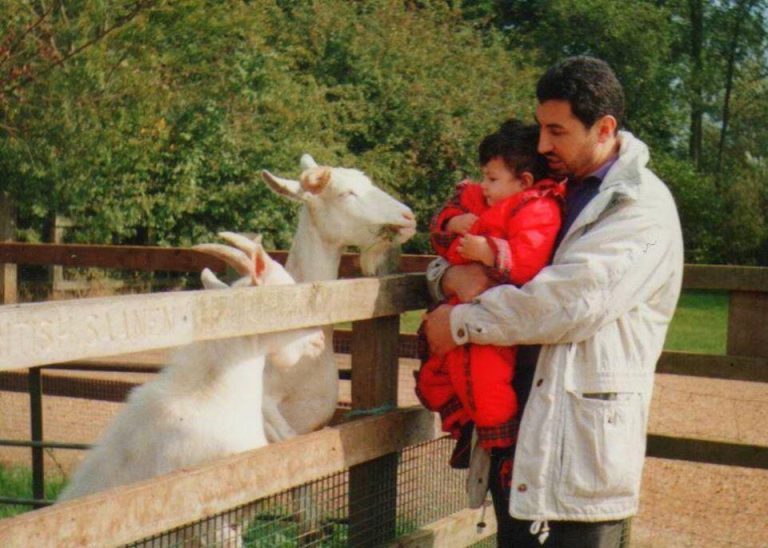

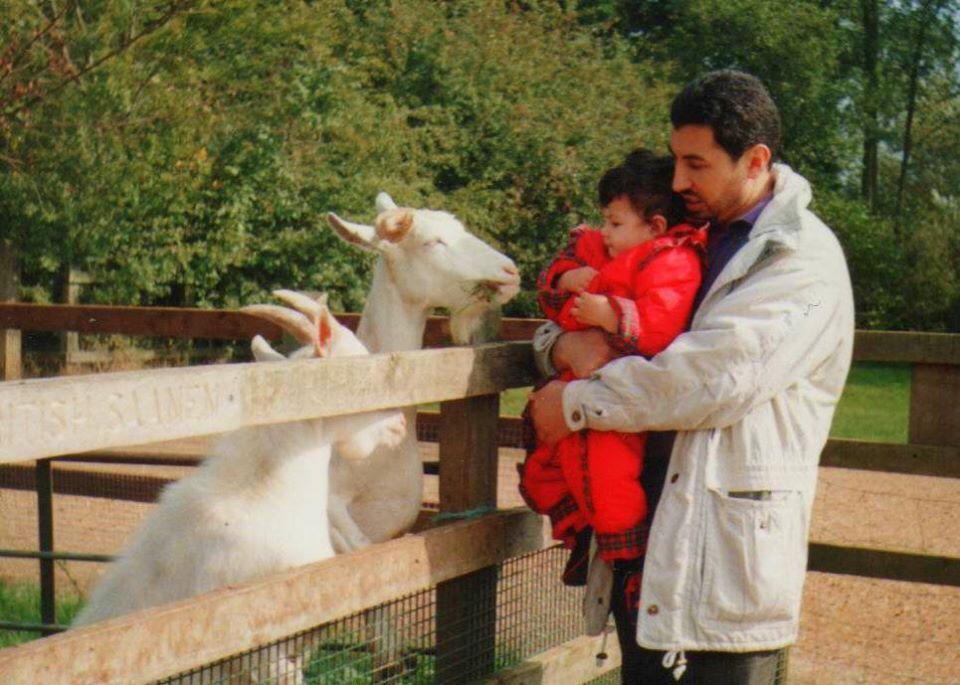

The Scruffs (as my terriers are known) have a had a Small Dog Conference on our way here, with a surprisingly game sausage dog. They scamper about, wiggling to a soundtrack of bleating sheep over the river. I watch the doglets adoringly, the way we do. I hazard a guess at how much the flock of sheep weighs. The combined mass of all us people, in our sensible outdoor clothes.

Bigsweir Bridge

The journey up the river to Bigsweir is longer than anticipated. It’s 2pm and I am out of snacks.

We meet a man with his two kids, picnicking. One child asks if there are buttercups, but the parent says it’s too early.

Then I spot one, and then another. I let them know. The whole field appears buttercupped then, luminous yellow and seeking chins.

The man says to look out for a collie in high-vis, who’d taken off after a herd of deer earlier. One smaller biomass displacing so many others.

Our older dog, Barney, is thirteen now, and less agile; we’ll soon have to walk him separately. I think about how it isn’t the same landscape, depending on which body you’re in. How different the map is, compared to the actual walk.

Browns Convenience Store, Landed

Browns is also closed. Google Maps has no indicators of a nearby food source and, suburbanite that I am, I fear this means no food at all. Mercifully, The Sloop Inn is open and friendly, a lasagne now on its way.

The women serving at the Sloop say Browns is meant to reopen next year. I imagine the convenience store as featured in the show, its shelves full of unbranded tins, a bounty of product-placement-avoiding goods staged for the cameras. The crew probably went home with it, or it went back to a prop store. There are no empty stores, presumably, in utopias. No ‘food deserts’.

The lasagne is passable. My human battery is back to about 80%.

Sometimes I wonder if I am doing ‘being on a walk’ wrong— stopping to make notes, talking freely with the dogs or even with corvids, flying insects, or anyone else I encounter

Sometimes I wonder if I am doing ‘being on a walk’ wrong— stopping to make notes, talking freely with the dogs or even with corvids, flying insects, or anyone else I encounter. It seems perfectly reasonable for me to talk out loud to other living things, or even rivers. On some level, I believe they receive my communication…which is not the same as understanding what I am saying. On some level, I believe we are part of what Mary Oliver calls, ‘the family of things’.

We set off for Bargain Wood, the woodland through which Otis and Eric cycle to school. Except it isn’t, of course: the geography is all rearranged for the cameras.

Bargain Wood

We walk up, above the small road where, I believe, the cycling-to-school scenes are filmed. Next, we take a tantalising path uphill through the woods.

On the way, we pass three people in high-vis, hefting bags of lager cans, wielding litter-pickers. More high-vis, but this time of practical care.

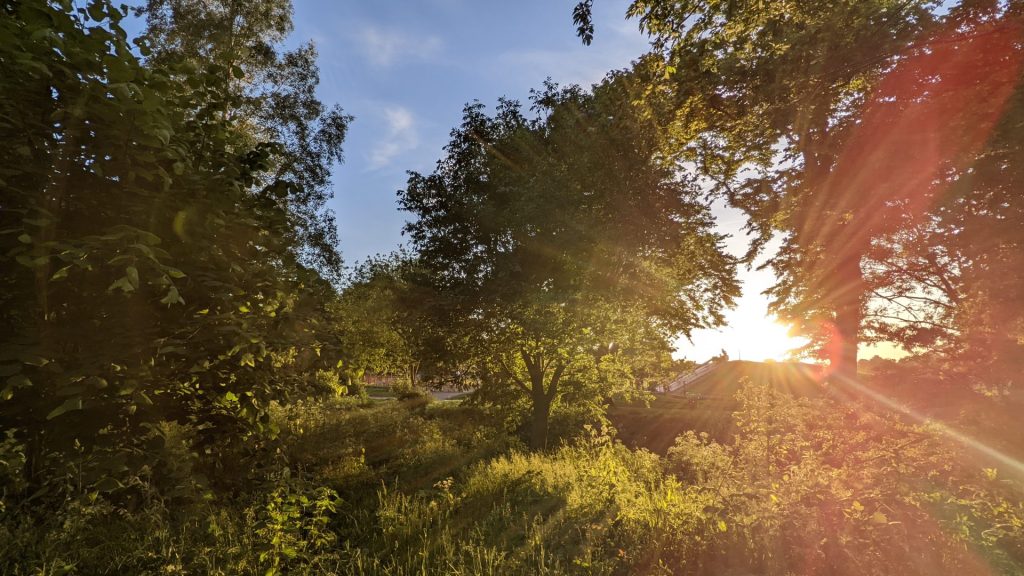

Barney struggles a bit up the hill. We take a quieter path and there is a moment where the afternoon sunlight is shining perfectly through the branches, just budding. A woodpecker is audible nearby, thwacking away. I sit on a log, listen.

It feels fairly utopian, except there aren’t any other people around. Being sat on this log, eyes closed, listening to a woodpecker, is about the most ‘me’ I can feel, I think. Whatever that means. Can you listen to a woodpecker queerly? (Thwack)

After the sublime, the inevitable ridiculousness; we lose the path, stagger down some very steep, probably-not-public paths, descend toward Tintern and close this loop.

I wonder what the montage of my walk today would be like. Was it a daytime TV feature, or a folk-horror yarn? How would the editing, the angles, tell a certain version of this story?

Walking and being alone outdoors, having access to this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty less than an hour from home feels utopian enough right now. Even with all its dog poo, its flags, the funny looks and the knowledge of thinning birdsong.

Perhaps that’s the queerest thing of all — to go out into nature, whatever that is, with all its troubles, all the troubles we bring it. To try and be together anyway, mincing through the wreckage, loving it all the same.

🐌

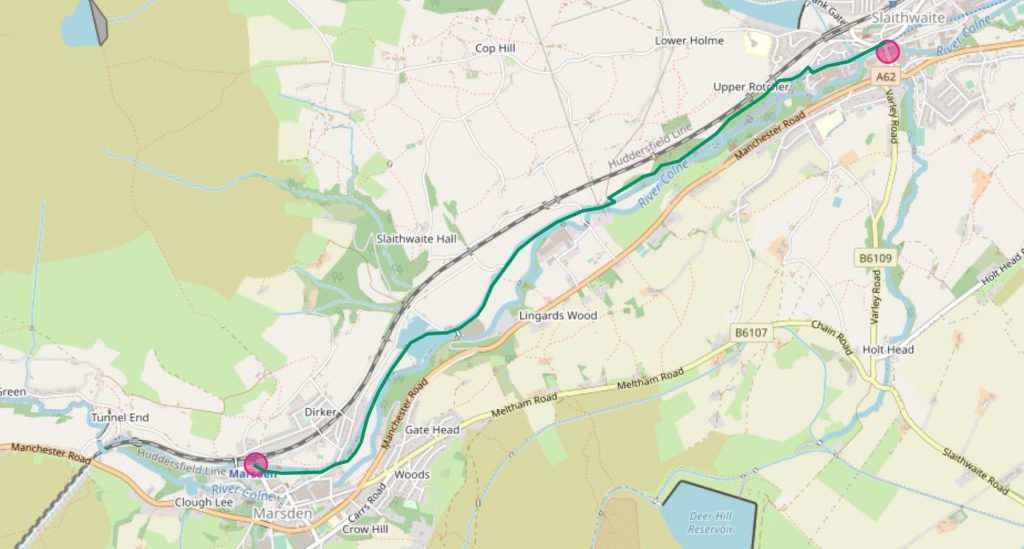

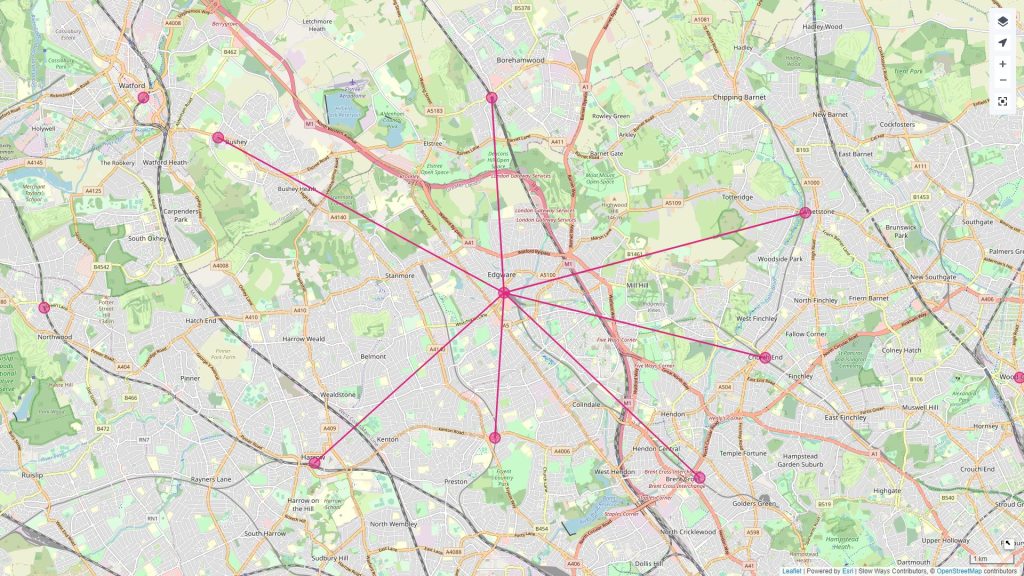

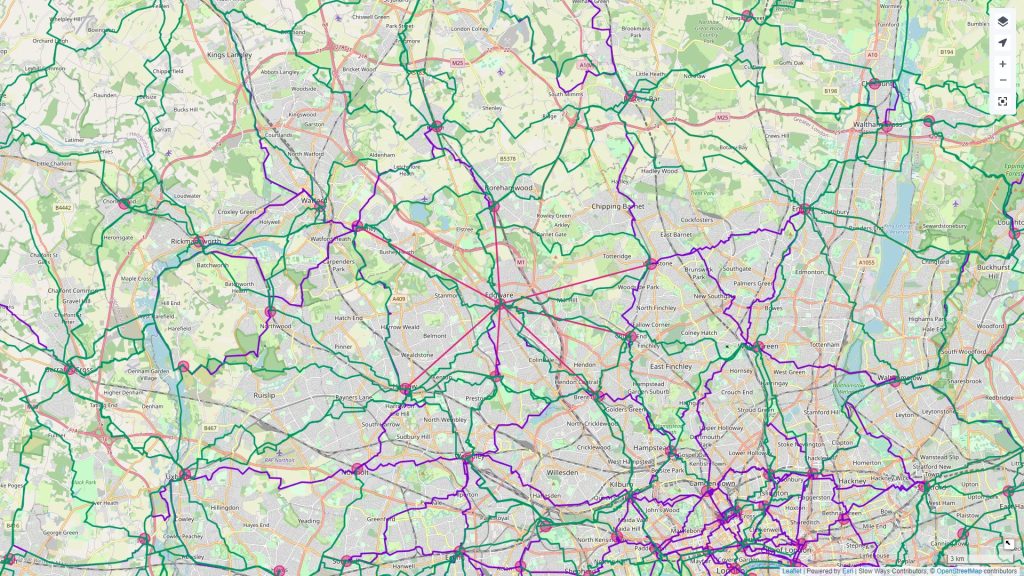

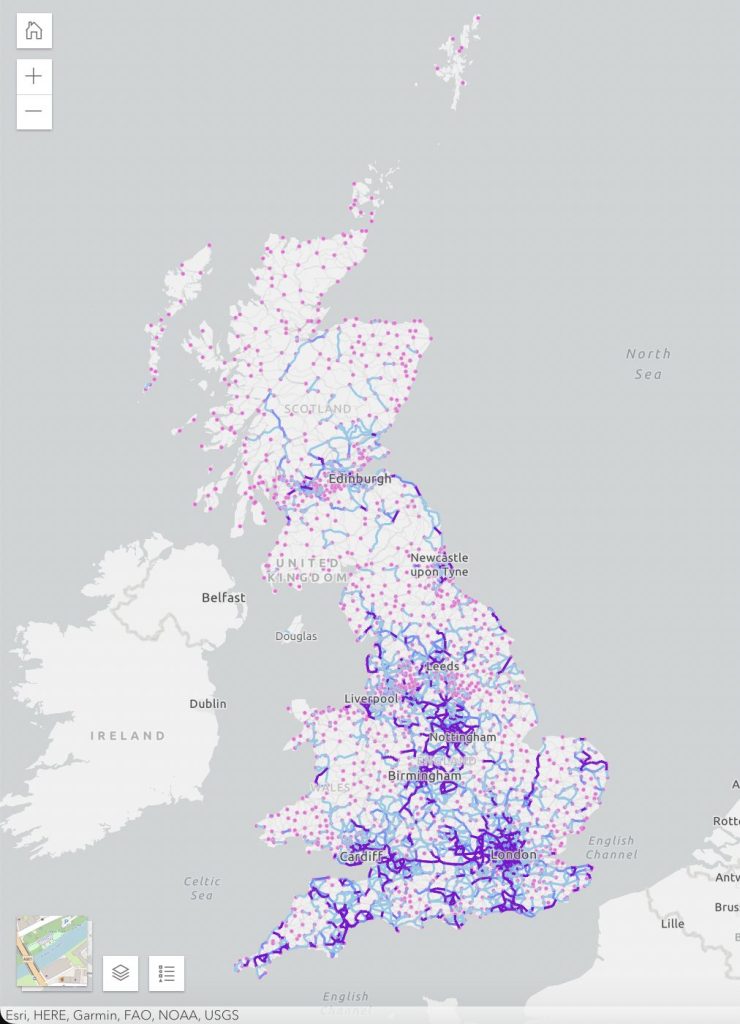

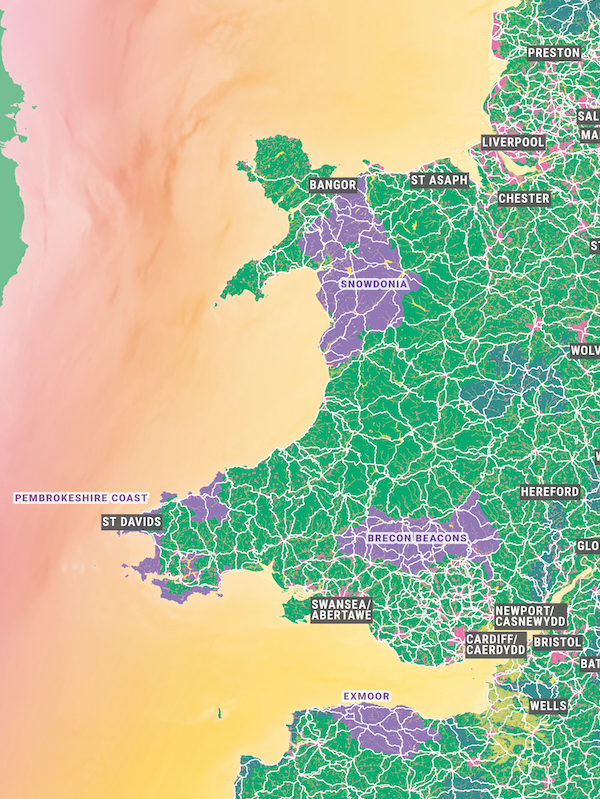

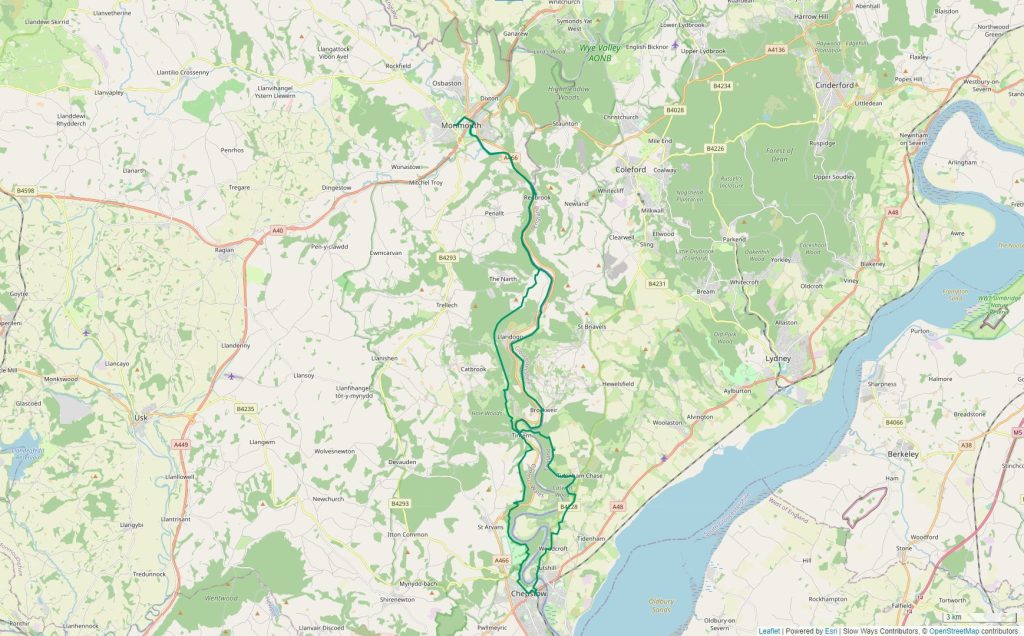

Caleb walked around the Tintern and Llandgo area of the Wye Valley, crossing the Wye’s bridges as he went. If you would like to try walking a Slow Way in the area, there are two Slow Ways routes between Momouth and Chepstow that will travel a similar route: Monche one and Monche two.

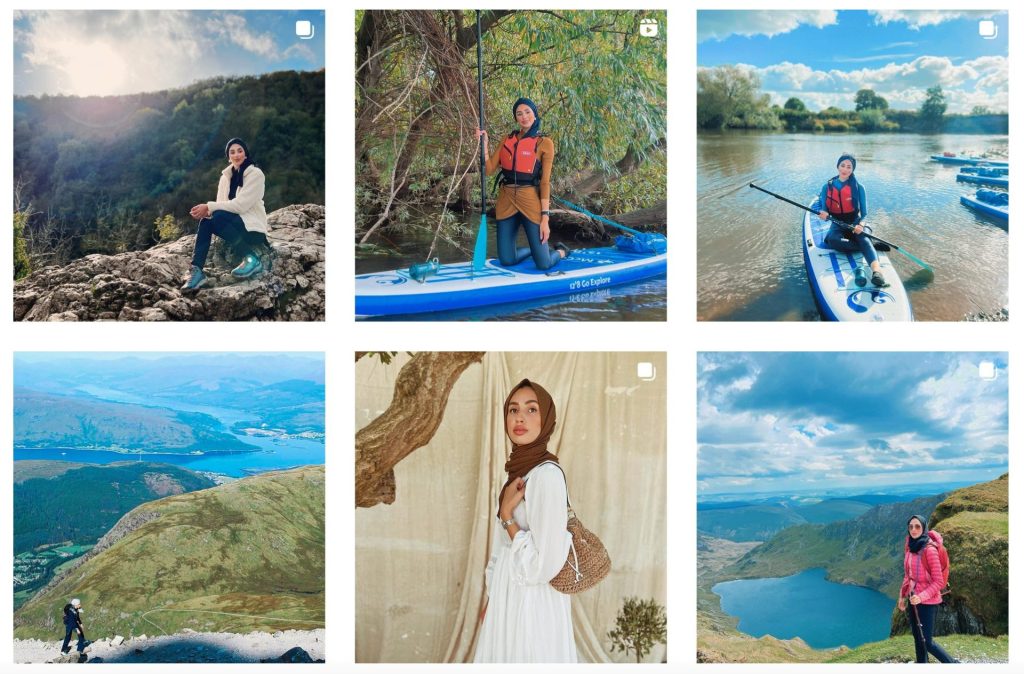

Caleb Parkin

Caleb Parkin is a queer eco poet & facilitator, based in Bristol.

He tutors for Poetry Society, Poetry School and First Story and holds an MSc in Creative Writing for Therapeutic Purposes.

From 2020 – 2022, he was the third Bristol City Poet. His book, The Fruiting Body, was longlisted for the Laurel Prize.